The scope of history today has expanded considerably. History is no longer a chronicle of kings. Still, historians have sought to include histories of everything, from classes that are regarded as marginal and insufficient to regions that are regarded as peripheral. Considering this scope of history, the writings in ancient India are very narrow in nature and scope. Many of them were written by literate men, generally Brahmanas, for the consumption of the ruling elite. Vast sections of the population find little or no place within such narratives.

Also Read: Chinese Historiography – Confucianism and Features

Greco-Roman Traditions of Historiography

It is very easy to dismiss these works on account of their limitations, yet it is worth mentioning that their significance has been debated for nearly two centuries and that a critical appreciation of the traditions within which these texts were located can enrich our understanding of the past.

The Vedic Danastutis (Early Histories)

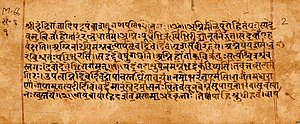

The earliest examples of the history of India are found in the Rigveda’s verses, called Danastutis, which means “In praise of God”. These verses were composed by the recipients, who were priests, and usually mention the name of the donors. The recipient prays for the well-being of the donor after acknowledging the gifts he receives. Such acknowledgements and proclamations were part of major rituals such as the Ashwamedha. As part of the ritual, a horse was let loose to wander for a certain period.

During that time, a priest would sing in praise of the patron every morning, while a kshatriya would sing the war-like exploits every evening. It seems that Vedic verses led to the development of many stories that were compiled in the epics and Puranas. It would be worth mentioning here that only what was regarded as positive and desirable from the point of view of the priest or the kshatriya found a place in such eulogies.

It can also be noted that the recalling of the generosity and prowess of the patron was not meant to be a simple, objective recounting, but was, in fact, meant to ensure the patron would continue to live up to expectations.

Are the Epics Historical Narrative?

The Mahabharata, which is regarded as an Itihasa (history), and the Ramayana, which is considered a mahakavya (great poem), can be analysed in terms of the genre they represent, as the events mentioned in them are unlikely to be established. The epics may date back to the early centuries of the 1st millennium BC. Archaeological excavations and explorations indicate that sites such as Ayodhya (mentioned in Ramayana) and Hastinapur, and Indraprastha (mentioned in Mahabharata) were small pre-urban settlements during this period.

It is worth mentioning that both the epics contain genealogies. The Mahabharata contains the genealogies of the lunar (chandravamsa) lineage, while the Ramayana has the genealogy of the solar (suryavamsa) lineage. Several ruling families in the early medieval period traced descent from these lineages. All these events and lineages may not be true, but they are important for what they narrate about socio-political processes.

Thus, these very early historical texts of Indian history. We will discuss other sources in the coming blogs.

Pingback: Puranic Genealogies in Early Historical Writings