Prasastis and Charitas of Early Historical Writings in India

The scope of history today has expanded considerably. History is no longer a chronicle of kings. Still, historians have sought to include histories of everything, from classes regarded as marginal and insufficient to regions considered peripheral. Considering this scope of history, the writings in ancient India, like Puranic genealogies, are very narrow in nature and scope. Many of them were written by literate men, generally Brahmanas, for the consumption of the ruling elite. Vast sections of the population find little or no place within such narratives.

Also Read: Puranic Genealogies – Historiographical Traditions in Early India

History – Historiographical Traditions in Early India

It is easy to dismiss these works due to their limitations; yet, it is worth noting that their significance has been debated for nearly two centuries, and a critical appreciation of the traditions within which these texts were situated can enrich our understanding of the past. Apart from texts, Prasastis was also an important source of history.

Courtly Traditions: Prasastis

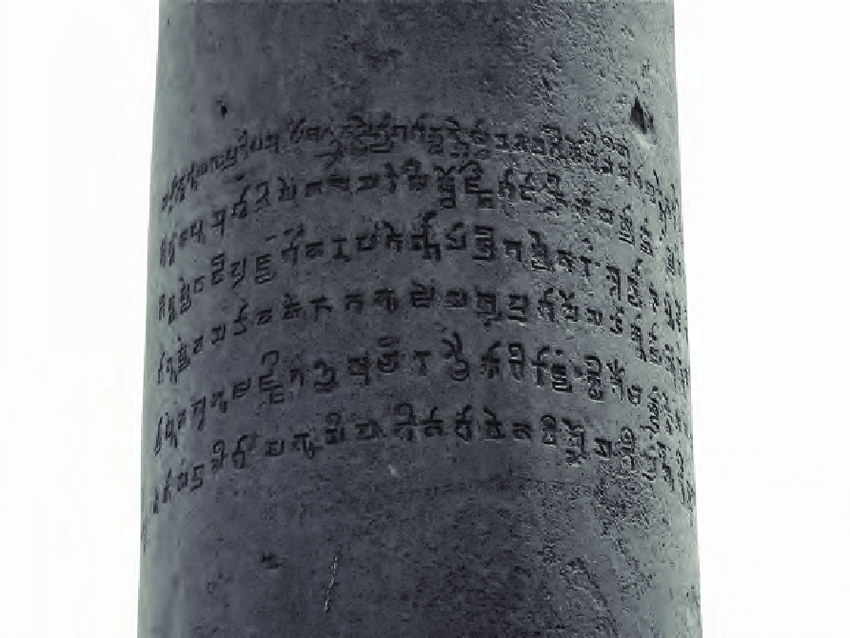

Prasastis are also historical records written as independent inscriptions during the 4th century CE. They are mainly eulogistic, commemorating the generosity of the royal donors, and are written in ornate Sanskrit using similes and metaphors. These inscriptions were circulated among an elite audience, mainly rulers and court staff. Some of the earliest examples of the Prasastis are in Prakrit; the best-known examples are in Sanskrit. Such inscriptions became particularly common from the 4th century CE.

These were often independent inscriptions but could also be part of motive inscriptions, commemorating the generosity of the royal donor. Samudragupta’s Prayaga Prasastis, also known as the Allahabad Pillar Inscriptions, is one of the best-known Prasastis, which was composed by Harisena, a skilled poet. It describes the rule of Samudragupta. Another famous Prasasti is that of Pulakeshin, the Chalukyan ruler of the 7th century CE, composed by poet Ravikirti.

It also describes Pulakeshin’s succession to the throne and his military exploits. The poet applied his skills to those of Kalidasa and Bharavi. Ravikriti’s composition is part of a votive inscription that also records how the poet donated a house for a Jaina teacher.

Courtly Traditions: Charitas

Charitas was meant to be a historical account of the lives and achievements of ‘great men’. Given the length of texts and styles of writing, which were ornamental, Charitas was for elite consumption. Most of the surviving examples of Charitas are in Sanskrit. One of the earliest Charitas that survives is the Buddhacharita, which was composed by Ashvaghosa in the 1st century CE. It describes the luxuries of courtly life, including elaborate descriptions of women. It seems it was meant for the Kushana court.

Harshacharita, another best-known Charita, composed by Banabhatta, provides an account of the early years of Harsh’s reign. Bana has carefully composed with ornamental Sanskrit to eulogize the ruler. A unique feature is found in the Ramacharita, composed by Sadhyakaranandin, for the Pala ruler Rama Pala of eastern India. The verses in it are written in such a way that each of them could be interpreted as referring either to the life of the epic hero or that of his patron.

Thus, Prasastis and Charitas are important sources of historical studies in India.